One of my favorite chefs happens to be eight. Like most kids his age, Joshua has giraffe-like legs and an absolutely infectious — and seemingly spontaneous — giggle. He’s the son of my friends, Jon and Beth. I’ve known Joshua most of his young life, and after seeing him in the kitchen, I can attest that what his father says is true: “He’s a good mix between both of us.”

Jon describes Beth as a traditional cook with a host of French cookbooks. If she wants to make French onion soup, she’s confident that the perfect recipe is within those covers. She has just one method for making lasagna: the way she learned in Bologna, Italy. According to Jon, “she figures there’s a right way for everything to taste. And a wrong way.”

Jon, on the other hand, embodies what some might consider the “wrong” way. He’s an experimental chef with a generous serving of eclectic added in for good measure. Once he made a hot dog, mustard and sauerkraut lasagna. I think there were mashed potatoes in there somewhere, too. He laughs, protesting that he only made it once. That said, he describes a recent dinner party he and Beth hosted. The object was to make “dishes that would make your Italian grandmother’s soul hurt.” Jon made massaman curry lasagna.

Well, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree; Joshua likes experimenting, as well. He made dinner when I visited a few weeks ago. He’d never cooked asparagus before, so I showed him how to cut off the ends and demonstrated a simple preparation with olive oil, lemon, garlic and a little salt and pepper. As I spread the green stalks out on a cookie sheet for the oven, I asked him if he would like to try adding anything else. His answer? Capers. Like father, like son. (It was delicious, by the way. And Jon says the Thai-inspired lasagna was a hit, too.)

While he likes to experiment, Joshua also seems to understand the importance of following a recipe, which his dad says is Beth’s influence. They cook a lot together, and you might be surprised by some of Joshua’s specialties, which include the aforementioned French onion soup and ratatouille. Yes, really.

The movie of the same name is what inspired this aspiring gourmand’s interest in the kitchen. After Joshua saw Ratatouille, sometime around 2008, he got a game for his LeapSter with the same theme that helped with counting. As we sit down for our interview, his dad jokingly asks, “What’s three times three?” But it brings up a good point — cooking builds math skills. “You need to know how many scoops and stuff to use,” Joshua explains.

On Sunday nights, Joshua makes dinner. And it’s a pretty wide selection of entree items: Waffles, pancakes, tacos, fish, hot dogs — and he’s made both pizza dough and tortillas from scratch. The thing he likes to do most in the kitchen is chopping things like onions or potatoes (see Chef Joshua’s tips below for keeping kids safe in the kitchen.)

Yeah, that’s enough to make any parent sick to their stomach. Jon says he wouldn’t like his son pulling out the knives unsupervised, but says Joshua is responsible about it. “I believe in safety through competence,” Jon says. Mastering the skill is something he is working toward, which is good, because Joshua says — with a giggle — that his goal is to be a chef in space someday.

To show off his cooking skills for you Eaters, Joshua offered his take on the shortbread cookies featured in April’s holiday gift post.  He followed the same recipe, measuring out and mixing in all the ingredients his Dad listed on an easel in the kitchen. Then it was time to get creative.

He followed the same recipe, measuring out and mixing in all the ingredients his Dad listed on an easel in the kitchen. Then it was time to get creative.

He wanted to try some fun stuff with candy that would be easy and interesting for other kids, so he formed small balls and filled a thumb print in the center of each with chocolate chips, Rolo caramel candies and mini Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups. He also made a version of the thumbprint cookies with chunky cranberry sauce and mixed sprinkles into another batch.

Then there was a more unconventional version: cookies made with a Maryland staple, Old Bay seasoning, complete with a 3-D crab sculpted by dad Jon. And surprisingly, they were pretty good. With a little less sugar in the dough and a bit of lump crab salad on top, I could totally see serving these as an hors d’oeuvre.

Then there was a more unconventional version: cookies made with a Maryland staple, Old Bay seasoning, complete with a 3-D crab sculpted by dad Jon. And surprisingly, they were pretty good. With a little less sugar in the dough and a bit of lump crab salad on top, I could totally see serving these as an hors d’oeuvre.

But for kids, mixing in the sprinkles is fun and festive. You could also put them on top by brushing the dough with an egg white wash and sprinkling them on top, which we tried, too. I also liked the cranberry version, and think swapping with jam would make these yummy. But in keeping with our gift-giving theme, if you pair any of these cookies with a plate hand-painted by your little chef, it doesn’t really matter what you put in them. They’re perfect.

And as for cleaning up? Joshua says, “That’s my parents’ job.”

He’s still got a lot to learn.

Chef Joshua’s Tips for Eaters: Kitchen Safety For Kids

- Protect your hands: When Joshua is cutting, he wears

the finger-tip oven mitts to hold the food he is chopping. “If I accidentally bring the knife down on top, I don’t cut off my finger, ” he says, adding that you should never play when using a knife.

- Cutting onions: There are lots of tips for how to prevent crying while chopping onions, but Joshua has one of the best I’ve heard: use goggles. Plus, he looks totally cool.

- Be careful around the stove: To test if a pan is hot and ready for food without getting burned, Joshua just flicks a little water into the pan. If it bubbles up and disappears, the pan is ready. And hot.

- Follow the recipe: “What do you know — it might explode when you cook it,” he says. There is a place for experimentation, and he says, “learn different strategies,” like substitution. Take Thanksgiving, for example. He worked with his parents to make four different kinds of cranberry sauce, substituting different ingredients for each version of the recipe. Note: substituting, not changing.

Assorted bottles with clear, burgundy and rose-colored liquids are scattered on one table. They stand next to a small barrel held in place with a wedge of wood on one side and a plastic spatula on the other. An assistant chops vegetables, occasionally stirring pots on the stove.

Assorted bottles with clear, burgundy and rose-colored liquids are scattered on one table. They stand next to a small barrel held in place with a wedge of wood on one side and a plastic spatula on the other. An assistant chops vegetables, occasionally stirring pots on the stove. Now, thanks to technological advances and a better understanding of the chemistry involved, vinegar making doesn’t take as long, Rausse says. You might not get that super thick stuff, or the complexity of flavor, but even Rausse says that many of the mass-produced commercial brands you get off the grocery shelf are pretty good.

Now, thanks to technological advances and a better understanding of the chemistry involved, vinegar making doesn’t take as long, Rausse says. You might not get that super thick stuff, or the complexity of flavor, but even Rausse says that many of the mass-produced commercial brands you get off the grocery shelf are pretty good. It all started in 1999, when Warren Brown began honing his baking skills by experimenting in his home kitchen. He was a full-time lawyer by day, so how did he find the time to fine tune all those cakes? Do all the trial and error that goes into getting the ingredient ratios and the temperatures just right?

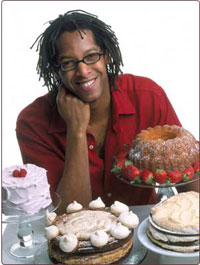

It all started in 1999, when Warren Brown began honing his baking skills by experimenting in his home kitchen. He was a full-time lawyer by day, so how did he find the time to fine tune all those cakes? Do all the trial and error that goes into getting the ingredient ratios and the temperatures just right?